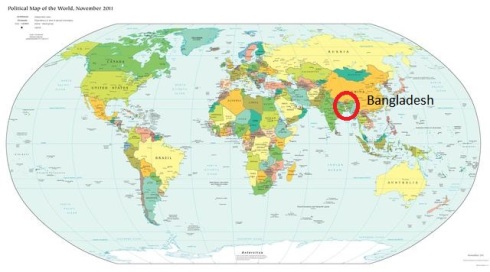

My daughters’ school held an event to celebrate the diversity of the student body. Parents could volunteer to put together a display of artifacts representing their culture. Since Bangladesh seemed likely to be more mysterious and interesting than the United Kingdom to Texan elementary school students, I offered to represent Bangladesh.

My daughters’ school held an event to celebrate the diversity of the student body. Parents could volunteer to put together a display of artifacts representing their culture. Since Bangladesh seemed likely to be more mysterious and interesting than the United Kingdom to Texan elementary school students, I offered to represent Bangladesh.

My parents are originally from Bangladesh; it was still part of Pakistan when they were born but was an independent country by the time they started their PhD work. I was born in the UK, where my father was teaching chemistry, and split my early childhood between England and Scotland. Our whole family moved to Bangladesh when I was nearly 8. I spent a decade there, in the capital Dhaka for the most part, although I spent a year in deep rural Bangladesh, at the orphanage my mother managed in Kurigram. I left Bangladesh for the US to go to college when I was 18 and have lived in the US since. I’ve been here nearly 16 years.

You’d think that spending 10 years in Bangladesh during key formative years of my childhood would bestow me with a deep degree of identification with Bengali culture, but it didn’t. I spent those 10 years feeling like a foreigner, likely in part due to my early childhood in Britain. The other contributor to my sense of alienation was that I lived with one foot in the expat community. Although my parents were Bangladeshi, and countless cousins were nearby, my life revolved around the American school I attended along with many embassy, UN, and non-profit kids from around the world. I felt little kinship to the few extremely well-off and entitled Bangladeshis who also attended the American school.

Let’s return to Texas in 2013.

The weekend before the diversity event at my twin daughters’ school in suburban Austin, I went shopping for clothes for my girls. We thought it would be fun for them to wear Bangladeshi clothes, but they’d outgrown all such outfits we owned. As luck would have it, I had run into a lady who lived near our home and imported traditional clothes from India. We went to her home to shop. M selected a shalwar kameez, J a lehenga. As usual, while they started the shopping expedition with the intent of getting matching outfits, they couldn’t agree on anything that they both liked.

The house where we were shopping was full of women and children, sifting through bright, bejeweled clothes. I spoke to the lady and gentleman of the house in Bengali; everyone else was speaking Hindi/Urdu, which I kind of understand, but don’t speak. I felt like a fish out of water. I didn’t know whether the girls were allowed to try clothes on. I didn’t know how to appropriately get the owner’s attention to ask. I had no idea what length of kameez or style of shalwar was fashionable. I committed a faux pas by whisking my checkbook out in the room where the clothes were laid out, instead of waiting until I entered the private office. I was wearing the clothes I’d worn to work: jeans and a solid coloured top. All the other women were in South Asian wear.

I’d felt similarly out of place when I’d attended the local Bengali New Year celebration a few weeks earlier. I’d intended to take my daughters with me, but their father and stepmother were suddenly able to spend the day with them, so I went without them. The only person I ended up having a real conversation with was the older sister of an old classmate from Dhaka, a woman who, like me, considered herself part-British and had married a white man. As she put it, “Our kids don’t even look Bengali.” Except when I was chatting with her, I felt like I was being judged, something I hadn’t felt since I was an awkward teenager. I was convinced that I was being sized up by the top to bottom looks some of the other attendees gave me. I was wearing a sweater dress, not a sari or shalwar kameez. I didn’t trust myself to drape a sari correctly, and I knew all the shalwar kameezes I owned would be terribly out of date. I smiled at strangers, as I would anywhere else in Austin. Unlike elsewhere in Austin, the smiles weren’t returned and no conversations took off, except with young, presumably Bengali-Texan, children.

When the diversity event came around at the girls’ school, I wore one of my old salwar kameezes, 12 years out of fashion. I put together a collection of trivia on Bangladesh on sticky notes, pulled up a looping slideshow of images from home on my laptop, and laid out my entire collection of saris and knickknacks on a cafeteria table. I made sandesh from cottage cheese, sugar, and cardamom, and I offered to show kids what their names looked like written in Bengali script.

The whole time, I felt like a fake. I may look the part and speak the language, but I’m not Bangladeshi in any meaningful way. Perhaps I never have been.

My daughters know that Bangladesh is part of their heritage, and that I used to live there, but they’ve never been. They understand only very basic Bangla. They don’t have a single Bangladeshi (nation) or Bengali (ethnicity) friend. On the rare occasion that I cook Bengali food, they won’t eat it. I sing the 4 or 5 Bengali songs that I remember quite frequently, but my Western classical repertoire runs into the hundreds of songs.

Have I failed my daughters? Should I teach them more about this culture that feels so foreign to me? Or if I try, will I just be faking it?

Sadia is a divorced mother of two who lives in the Austin, TX area. She works in higher education information technology.

Welcome to the American way……..everyone is FAKING it! Those “Irish”in NYC ? Born in the USA….never been to Ireland….those Polish people in Chicago? Same. You are an American….so you get to share in our ever curious game of heritage….who am I? where did we come from? Finally, the answer is obvious, you are not Bangladeshi….even if you do look like them and were born there….YOU are American…

I loved your post Sadia. Your story is very similar to mine, I am greek but only lived in Greece from 10 to 25 years old so I totally understand your concern of authenticity.

You can’t show you daughters something that you are not but you can tell them what you know about Bangladesh and its culture, what you have seen, what you like and even invite them to disvover together what is part of their heritage and I am sure they won’t judge you for not knowing all the bengali codes and being out of fashion 😉

Eventually they will face the same problem as you do, people where ask them where they are from and they might need to go through lengthily explanations. I think teaching our kids about authenticity is more important than ethnicity.

You are not a fake, you are special.

Thank you for sharing your story. Your girls are gorgeous!

I have raised my kids overseas in another culture and haven’t lived in my own country since I was 20. Much has changed since I left

and sometimes I wonder if I really ‘know’ my culture well anymore. But even if it is diluted,

sharing our cultures with our kids enriches them. I think you’re doing a fine job!

Last semester, I studied the tension between multiculturalism and the North American way of life. We tend toward a sort of sari, samosa and steel-drum approach to “cultural heritage” days at school, which can often lend a superficial (if not stereotypical) idea of how a given cultural group lives their lives, even though we know that even the most “homogeneous” cultures have so much diversity in individuals’ world-views and cultural practices. But, then, how else could it be presented and taught for a bunch of kids in ten minutes or less, right? And how can it be done for ourselves – multi-ethnic, bi-racial parents of mixed-race kids in the culturally homogenizing information age? I think we need to allow that there is no one right way to be multi-ethnic, even if we look the part of a particular racial group. And then we need to cut ourselves some slack. Your daughters look beautiful, and it must have been a hill of fun for them. Those are the things I focus on when showing my kids bits and pieces of their Nigerian/Jamaican/Scottish/Irish/German/British heritage. Hopefully, when their older, they will choose the bits they love the most and make them into traditions. 🙂

Sadia,

I too have struggled with this authenticity issue for a long time. Zambian/ Indian descent, and then left Zambia at 17, barely went back, and after age 5 mainly part of and international school / expat community in Lusaka.

I relaxed on it all a bit more recently and show and offer my kids what I can of every culture I belong to. I struggle with it being shallow. But then, they get something else by being a part of our diverse circumstance. And they will dig deeper into what interests them I hope.

Really enjoying your posts. Thanks for sharing, and keeping this blog alive! Hope to read more.

I enjoyed reading your post. The personal account, the exploratory voice, the honesty. But what I enjoyed most were the doubts, the lack of certainty and the absence of complete faith in a very fixed narrative about multiculturalism that so many expat stories in the US convey. Your account was complex, nuanced and plural as any account of anyone’s life naturally is. I’m Bengali from Calcutta and was pretty sure of who I was myself until now after about 13 yrs in the US when during recent visits home I see less and less of the Calcutta I used to know and more of many new things. So I am less and sure sure of any statement I make about my hometown nowadays. But isn’t that true of everything? It’s only simplistic to think that people/ identities/ countries/ ethnicities can be so simply depicted via a saree or a curry dish or an iconic song or a word! Your daughters are kids. Just girls. Isn’t that enough?